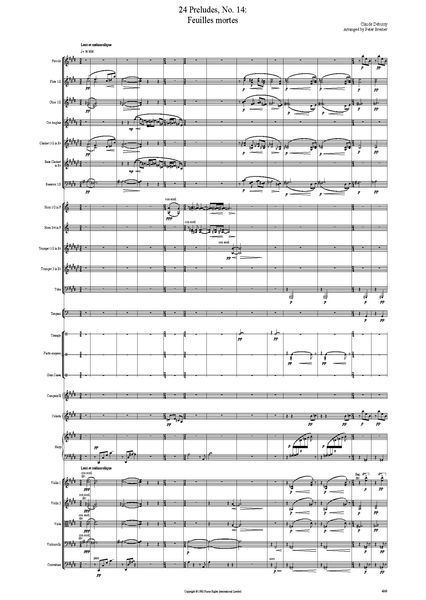

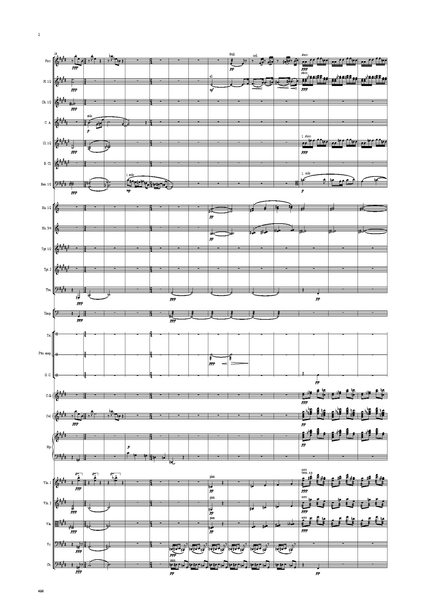

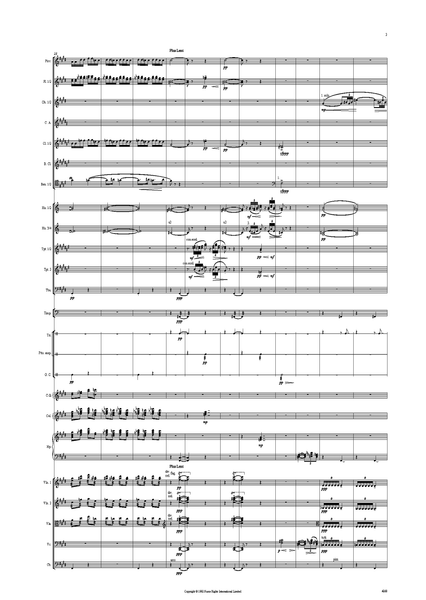

Claude Debussy: 24 Préludes, No. 14: Feuilles mortes – arranged by Peter Breiner (PB031)

Sheet music edition. Choose your format from the selection above.

4 pages

Duration: 3m

Instrumentation: 2+1, 2+1, 2+1, 2 – 4, 3, 0, 1 – timp - perc - cel - hp – str

As a composer Debussy must be regarded as one of the most important and influential figures of the earlier twentieth century. His musical language suggested new paths to be further explored, while his poetic and sensitive use of the orchestra and of keyboard textures opened still more possibilities. His opera Pelléas et Mélisande and his songs demonstrated a deep understanding of poetic language, revealed by his music, expressed in terms that are never overstated or exaggerated.

Debussy’s poetic sensibility and his delicate use of keyboard nuances, developed from Chopin, is shown clearly enough in the two books of Préludes, the first completed in 1910 and the second in 1913. For the present recording the Slovak-born composer Peter Breiner has orchestrated the pieces, revealing even more of the latent intricacies of the Préludes, hidden inner melodies made subtly evident in orchestral guise. The Préludes were originally published with titles given only at the end of each piece, suggesting that these were not absolutely essential to the performer. Danseuses de Delphes (Dancers of Delphi), a title that suggests the influence of Satie, was inspired by a caryatid seen at the Louvre. Marked Lent et grave, the mystery of Delphi is solemnly evoked in a series of chords that make clear the static nature of the dancers at the oracle. This is followed by Voiles (Sails), which carries the direction Dans un rythme sans rigueur et caressant, a characteristic depiction of a calm and distant seascape, although the title may also mean ‘Veils’. It makes typical use of Debussy’s original harmonic idiom and the whole-tone scale. The third Prélude, Le vent dans la plaine (The wind on the plain), offers a delicate tissue of sound, reaching a climax before finally dying away to a sustained final note. “Les sons et les parfums tournent dans l’air du soir” is suggested by Baudelaire’s poem Harmonie du soir (Evening Harmony):

Voici venir les temps où vibrant sur sa tige Chaque fleur s’évapore ainsi qu’un encensoir;

Les sons et les parfums tournent dans l’air du soir; Valse mélancolique et langoureux vertige!

(Here comes the time when, quivering on its stem, every flower melts away to vapour like a censer; sounds and scents turn in the evening air;

sad waltz and languorous dizziness!)

The poetic association with Baudelaire indicates something of the mood of the piece, with its the final suggestions of a distant horn-call. Les collines d’Anacapri (The hills of Anacapri) is allusive in its depiction, with inner melodies now further clarified, while Des pas sur la neige (Footprints on the snow) offers a cold, snow-covered landscape, suggested by the recurrent rhythmic figure, which, as the composer directs, should be the musical equivalent of a sad and frozen countryside, an image that, in language at least, must suggest Verlaine’s Dans le vieu parc, solitaire et glacé/Deux formes ont tout à l’heure passé (In the old park, lonely and frozen, two forms have just passed), the last of the Fêtes galantes that Debussy had set on various earlier occasions.

The mood changes with the menacing and stormy Ce qu’a vu le vent d’ouest (What the west wind has seen), followed by the gently expressive portrait of La fille aux cheveux de lin (The girl with flaxen hair), one of the most familiar of the Préludes, variously transcribed. La sérénade interrompue (The interrupted serenade) opens with a passage suggesting the preparation of the guitar for playing, an introduction to what follows, with rapidly repeated notes evoking the same instrument and Spain, the country with which it is generally associated. La cathédrale engloutie (The submerged Cathedral) returns to medieval France, with harmonies and modal writing derived from early organum, a device used at the opening of Pelléas. The textures evoke through the sea-mist the mystery of the ancient cathedral of Ys, its chant and the sound of its bells, drowned now beneath the waves that have engulfed it long since, according to legend. A mood of a very different kind is embodied in La danse de Puck (Puck’s dance), capricious and light-footed, presumably inspired by the Robin Good- fellow of Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream rather than Kipling’s creation, although it seems that Debussy was also familiar with the latter. The First Book ends with Minstrels, inspired, it has been said, by a black street-band that Debussy had heard in Eastbourne in 1905.

It seems that Debussy was determined to complete two books of twelve Préludes each. Apparently he regarded these as of uneven quality, a judgement in which others have concurred, and was apparently not happy to have them played one after the other. Nevertheless the two books of Préludes do make two effective and coherent wholes, whatever the composer’s original intentions, with the heart of each book at its very centre. The Second Book opens with Brouillards (Mists), in which some have seen the counterpart of paintings by Whistler or even by Turner. Feuilles mortes (Dead leaves) is marked Lent et mélancolique (Slow and melancholy) and is autumnal in its colours. The atmosphere is at once lightened by La Puerta del Vino (The Wine Gate), a habanera suggested by a postcard from Manuel de Falla showing the Alhambra gateway of the title. Debussy’s wide terms of extra-musical association appear again in “Les fées sont d’exquises danseuses” (“The Fairies are exquisite dancers”), its title apparently quoted from J. M. Barrie’s Peter Pan in Kensington, a book given to Debussy’s daughter Emma-Claude, known as Chou-Chou, with illustrations by Arthur Rackham. It was an illustration that gave the Prélude its title and character. Bruyères (Heaths), calm and gently expressive, paints a gentle picture of the open country, while General Lavine – eccentric, offers a cake-walk, depicting the American clown Edward Lavine, who appeared at the Marigny Theatre in the Champs-Elysées in 1910 and 1912.

La terrasse des audiences du clair de lune (The terrace of the audiences of moonlight) adapts a newspaper account of the coronation of King George V as Emperor of India, en- dowing the words of the report with an air of oriental mystery. With Ondine, the mermaid whose love of a mortal, who betrays her, brings him disaster, is again inspired by an Arthur Rackham illustration to a translation of Friedrich de la Motte Fouqué’s fairy-story Undine. Hommage à S. Pickwick Esq. P. P. M. P. C. is a tribute to Samuel Pickwick, the subsequent letters presumably standing for Perpetual President Member of the Pickwick Club. The English national anthem is heard below, as the piece opens, although what follows suggests the intrusion of Sam Weller in livelier adventures. Canope, very calm and gently sad, with its title an allusion to ancient Egypt, makes subtle use of the resonances implicit in the overtone series. It is followed by Les tierces alternées (Alternating thirds), the only Prélude with a title that only indicates its musical substance, originally a study in rapid thirds, but here with figuration adapted for the orchestra. The Préludes, now an orchestral showpiece, end with Feux d’artifice (Fireworks), a display of fireworks, suggesting a celebration in some city park, which allows, before the end, the distant sound of a fragment of the Marseillaise to be heard.

Keith Anderson

Audio Sample